Join our Facebook Group

Irrational escalation

Escalation of commitment, also known as illogical escalation of commitment, is a term that refers to irrational decision-making based on earlier reasonable assessments. This is a term that may be found in various domains, including psychology, game theory, economics, and philosophy. The use of escalation of commitment to explain previous acts is common. Someone who is gambling and decides to wager everything they have on one more hand in a card game illustrates this. This sort of maneuver can spell the difference between making a fortune and losing everything. Because the individual may have previously made more sensible judgments that paid off, the person now begins to make illogical decisions. It's the end of the week, which means we've concluded our series of financial, mental errors. If you've been reading all week, you've undoubtedly noticed that many of these mental faults seem to derive from the same underlying problem: your brain is terrible at forecasting the future. You preserve everything in the hopes that it will appreciate, or you make irrational predictions.

Irrational Escalation of Commitment

As a result of earlier commitments, you increase your commitment when you spend time and money on a course of action. You've increased your commitment to a goal if you've ever tried to climb a mountain (or attempted to achieve any other physical or mental peak) and pushed yourself to go a little further 'since I've already gone this far.' When the advantages from achieving your objective come nothing close to repaying the costs you've paid to get it, such escalation becomes illogical. Irrational escalation of commitment is exemplified by a business strategy that has already cost more than it can recover yet is still pursued.

If all of this sounds a lot like the sunk cost fallacy, you're right; an irrational escalation of commitment frequently occurs when people (or groups of people, such as businesses and governments) refuse to see or acknowledge that the money they've already spent is sunk, and insist on more spending to justify the initial spending. It creates a never-ending cycle of increasing spending to justify previously incurred losses.

Where this bias occurs

Assume you're a first-year university student focusing on anatomy and cell biology. You've always regarded science as your passion, so no one was surprised when you decided to pursue it. You took an optional course on the history of modern Europe during your first semester. While you loved your fundamental anatomy lectures, you discovered that your history lesson was the most enjoyable of all. You liked it so much that you chose to take several additional history classes in your second semester.

A voice in the back of your mind has been urging you to alter your major and pursue a Bachelor of Arts in History throughout the year. This decision, though, contradicts your long-term objectives and everything you've ever claimed about yourself. Although there's nothing wrong with changing your opinion, you feel compelled to do so. Commitment bias is the reason you're hesitant to alter your major, even if it's what you want to do.

Irrational Escalation of Commitment Examples

The dollar auction is the most often recognized example of an unreasonable escalation of commitment. The short story is that a lecturer gives one dollar to the class's highest bidder. However, there is a catch: not only will the top bidder be required to pay his price to get the dollar, but the second-highest bidder will also need to pay his bid to receive nothing. The bidding begins with a modest price of one cent and gradually rises until someone offers one dollar. That should be the end of it; after that, people are bidding more than the dollar is worth; therefore, the bidding should come to a halt.

However, because the second-highest bidder must also pay, he has an incentive to bid even higher; if he wins with a price of $1.01 rather than losing with a bid of $0.99, he will only have to pay one cent instead of ninety-nine cents. The dollar bidder is motivated in the same way: if she wins the auction, she will spend less than if she finishes second.

They may bid the dollar price up to many, many multiples of its true value with this seemingly reasonable concept behind them, only stopping when one bidder runs out of money to make increasingly larger bids or the professor calls the auction off. The bidders were optimizing their financial interests with each offer. Still, the total procedure might wind up costing each of them significantly more than the worth of the prize they're pursuing, presuming the professor compels them to pay up.

As previously stated, irrational escalation of commitment occurs when management chooses to continue a project after spending more money than it can recover. It may be done to save face or even the manager's job, but the procedure is inefficient and harmful for the organization.

Many types of 'Keeping Up with the Joneses' might be deemed illogical escalation of commitment; for example, even if you 'win' and have a more stunning vehicle, yard, or house, you have still spent more than you could ever expect to recoup by selling.

Beating Irrational Escalation of Commitment

So, if you're ever in an economics class and your professor asks you to bid on a $1 note, don't do it! Keep the perspective objective in mind when using more real-life examples, and attempt to keep your costs far below the potential returns. If you're attempting to win a $100 grand prize in a costume contest, your outfit(s) should cost less than $90; otherwise, even if you win, you won't have anything to show for it.

Also, be aware of when your expenditures have been sunk and are prepared to walk away. Yes, committing a little more money to your so far unsuccessful project could help it succeed, but it won't bring back the money you've already spent. Attempts to rationalize that spending is more likely to result in additional spending in the future with no increase in benefits.

The key to avoiding irrational commitment escalation is to be as logical as possible, focusing on the anticipated rewards rather than the expenses you've already spent. Remember, you can't alter what happened in the past, but you can affect what happens in the future!

Causes

According to one popular hypothesis concerning escalation of commitment, our need to be regarded favorably by others is a likely explanation for this phenomenon. We don't want to confess that we made a bad judgment, wasted our time, or appeared inept and inadequate in any way. We like regularity and stability, and clinging to these things is simpler than abandoning ship.

By spending resources on a failing project, we may assume we are pursuing a rational path of action. After all, if we "give up," all of our prior investments would be for naught. But if we keep pushing forward with the expectation that our efforts will be successful, the cumulative resources will eventually pay off. Our perspectives and judgments may cause us to miss the fact that we're on the incorrect route. Because we are so close to the problem, we get tunnel vision. We don't see the value in attempting something new, so we continue to do things the same way we've always done them.

Why is it difficult to stop?

Commitment escalation is a well-known issue. We've been taught that just because something is difficult does not mean that we should give up. Quitters are not well-liked in society! Is it preferable to let up too soon or to hold on too tight? We've been conditioned to believe that giving up too soon is a terrible thing.

Surprisingly, research suggests that the predicted drop regret has a larger influence on the commitment to a failed course of action than the actual drop regret. Expected regret decreases commitment. Another study backs up these findings, suggesting that optimism motivates people to keep going more than fear. In this study, the entrepreneurial teams continued as long as they believed in a favorable outcome.

Why it is important

Being conscious of commitment bias is beneficial in a variety of ways. We may start working to avoid it once we are aware of it. Because this bias can lead to poor judgments, avoiding it might be beneficial. Dismantling this prejudice is a good place to start when it comes to personal development because it helps us confess when we've made a mistake and learn from our mistakes.

Robert Cialdini's Six Principles of Persuasion describes a second way that understanding commitment bias might assist us. When used responsibly, Cialdini outlined six principles that might help you become more persuasive. Consistency is one of these principles, and it is a component that underpins commitment bias. Cialdini noted that getting individuals to make a little commitment early on increases the likelihood that they will agree to make a greater commitment later.

There are a variety of situations in which understanding commitment bias might be beneficial. It can help with everything from closing a transaction to getting someone to go to the doctor regularly.

Example applied

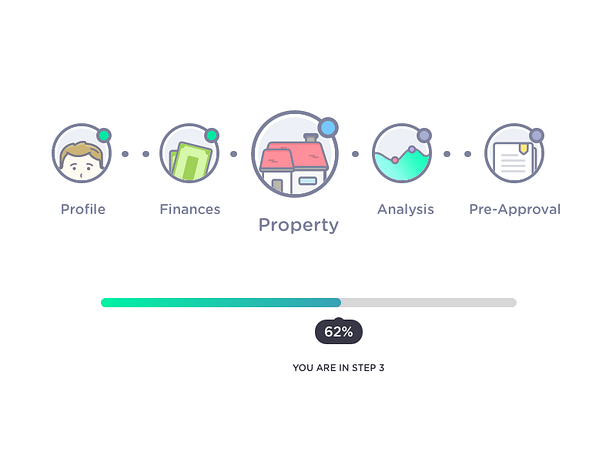

Showing users that they have already committed towards a particular action, will tend to have them continue their investment to the goal.

- Progress bar

- Subscription-based pricing model with recurring charges

Example of hypothesis applied

If we add a progress bar, then conversions for all users on mobile devices will increase, because of irrational escalation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Will you use psychology for your experimentation process?

Are you curious about how to apply this bias in experimentation? We've got that information available for you!

Join over 452+ users

- Lifetime access to all biases

- Filter on metrics, page type, implementation effort

- More examples and code for experimentation

Choose your subscription!

Pay with Stripe

Lifetime deal PREMIUM

Get access to the search engine, filter page, and future features.